In Conversation With… Ms. Anneli Skaar

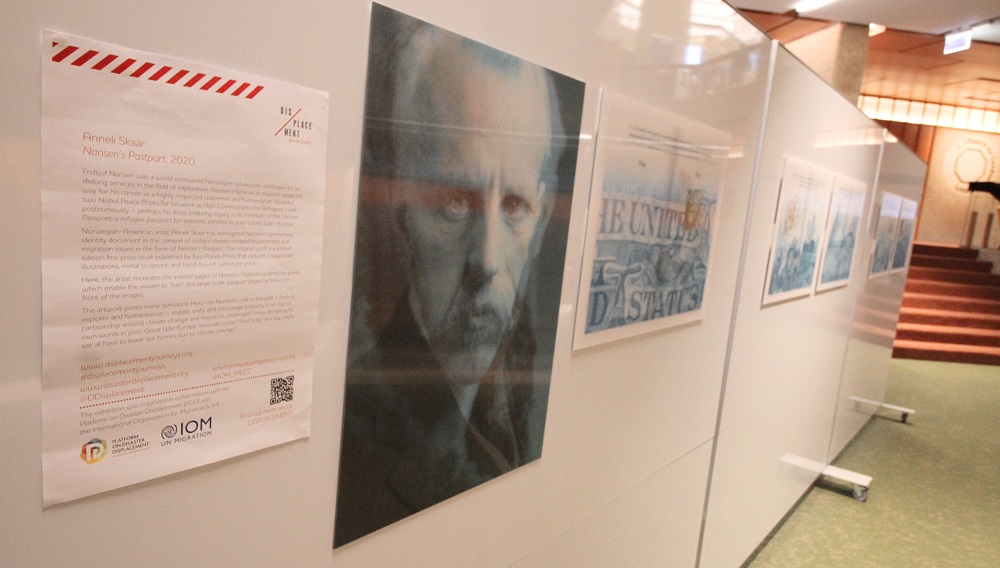

During the Global Forum for Migration and Development (GFMD) Summit in Geneva in January 2024, PDD partnered with DISPLACEMENT: Uncertain Journeys and IOM to present a Marketplace booth exhibition that featured contemporary and socially engaged art projects that seek to spark conversations on migration and development policy challenges and solutions related to disasters and climate change.

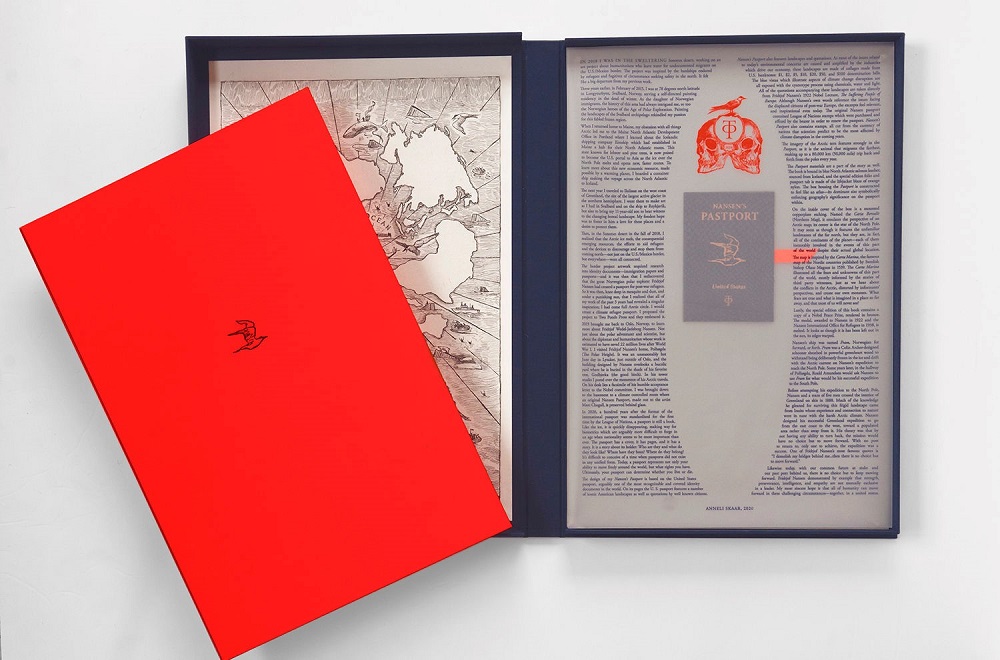

In Nansen’s Pastport, artist Anneli Skaar reimagines Fridtjof Nansen’s eponymous identity document, the Nansen passport, set in the context of today’s climate-related displacement and migration issues. The original work is a limited edition fine press book published by Two Ponds Press that includes copperplate illustrations, metal sculpture, and hand-bound cyanotype prints. For the exhibition at the GFMD, the artist recreated the interior pages of Nansen’s Pastport as lenticular prints, which enabled the viewer to “turn” the large-scale passport pages by moving in front of the images.

The artwork poses many questions: How can Nansen’s role in the past – both as explorer and humanitarian – inspire, unify, and inspire empathy in an age of partisanship around climate change and migration challenges? How do Nansen’s own words in post-Great War Europe resonate today? And lastly: one day, might we all have to leave our homes due to climate change? In a follow-up exchange with the artist, she shared her perspective about art, politics and the environment, her most memorable response to her work on this issue, and more.

PDD Secretariat: What first inspired you to connect art, climate change and displacement?

Anneli Skaar: I connected art, climate change, and displacement by accident. In 2015, I did an artist residency in Longyearbyen, Svalbard, with the intention of creating a series of painted arctic landscapes. While I was there, I felt and saw the impact of climate change, and learned so much about it from the local community that I was in contact with. Along with a lot of paintings, I ended up writing a travelogue on my experience, called The Sh•ttiest Coffee at the Top of the World which addressed a lot of the issues I experienced there, albeit in a tongue-in-cheek and accessible narrative. From then on, the subject of climate crisis issues—and especially displacement—became a strong influence on my work. I did a fine press book in 2016 called Bears and Ruins based on my experience in Svalbard, and in 2018 I did a project called The Other with fellow artist Mark Kelly which dealt with undocumented migration on the southern border. That project would directly result in creating my artist book Nansen’s Pastport in 2019-2020, and also The Island Whale, created in 2022.

Anneli Skaar: I connected art, climate change, and displacement by accident. In 2015, I did an artist residency in Longyearbyen, Svalbard, with the intention of creating a series of painted arctic landscapes. While I was there, I felt and saw the impact of climate change, and learned so much about it from the local community that I was in contact with. Along with a lot of paintings, I ended up writing a travelogue on my experience, called The Sh•ttiest Coffee at the Top of the World which addressed a lot of the issues I experienced there, albeit in a tongue-in-cheek and accessible narrative. From then on, the subject of climate crisis issues—and especially displacement—became a strong influence on my work. I did a fine press book in 2016 called Bears and Ruins based on my experience in Svalbard, and in 2018 I did a project called The Other with fellow artist Mark Kelly which dealt with undocumented migration on the southern border. That project would directly result in creating my artist book Nansen’s Pastport in 2019-2020, and also The Island Whale, created in 2022.

PDD Secretariat: How do you think art helps further the global response to disaster displacement?

Unfortunately, people generally don’t act on things unless they can feel it on their own body and in their own lives. You see people all the time who have been passive or nonchalant about issues and suddenly become moved to action when things happen to them or someone they are close to. To get people to engage is hard when issues are far away and happening to others. Because art is a subjective, visceral, and immediate experience, it has the power to become personal.

PDD Secretariat: In this current climate, the relationship between art, politics and the environment has gotten increasingly complicated. How do you see your role as an artist in this equation?

Anneli Skaar: I think the relationship between art, politics, and the environment has become increasingly complicated, mostly because of vested financial interests and a general distrust in science, which is unfortunate. There’s a terrific quote by Lin Manuel Miranda in an Atlantic article which hangs on my fridge, handwritten by a friend with whom I had a discussion on this very question.

Miranda said “All art is political. In tense, fractious times—like our current moment—all art is political. But even during those times when politics and the future of our country itself are not the source of constant worry and anxiety, art is still political. Art lives in the world, and we exist in the world, and we cannot create honest work about the world in which we live without reflecting it. If the work tells the truth, it will live on.”

PDD Secretariat: What was the most memorable response to your work on these issues?

PDD Secretariat: What was the most memorable response to your work on these issues?

Anneli Skaar: My publisher Two Ponds Press and I launched Nansen’s Pastport at a fine press fair in March 2020, literally days before we all went into lockdown. It’s an artistic reinvention of Norwegian explorer and humanitarian Fridtjof Nansen’s refugee passport created in 1922, in the context of climate migration and displacement. Most of the promotion for this project took place online and, because of this, we probably engaged with and reached more people than we would have otherwise.

One of these people was a Russian woman in Friendship, Maine.After one of my online talks, she wrote me a lovely email, with an open invitation to her home for tea. Her grandparents had escaped Russia and they had Nansen passports, so the topic of my book resonated deeply with her and her artist husband. Naturally, 2020 was a year I wasn’t feeling comfortable about going anywhere, let alone the home of someone I didn’t know, and the invitation was politely put off until the global situation changed. In 2021, I heard from her and her husband again, and at this time I felt more comfortable about a visit, but I was probably the busiest that I have ever been in my life, and was too burned to a crisp emotionally to even make dinner let alone make social visits.

Again, I put off the meeting until a better time.

In early 2022, I heard from her again, and this time she had bad news. Her husband had died in the fall, from cancer. She invited me out to Friendship again. This time I said yes.

I found her in a charming house at the edge of the water, at the end of a long dirt-covered driveway. The rooms were filled with art, much of it by her late husband who carved birds and other animals out of found objects. There were books everywhere, and seedlings in little containers by the window.

“There’s nothing more optimistic than planting seeds,” she said.

The table was set for tea, with “Poor Man’s Caviar” and powdery Russian tea cakes. Photos and old paperwork covered the table in between the dishes. We talked about her history, and about Ukraine which had very recently been invaded. Each time she mentioned the horror of the Russian invasion she broke down crying. She was devastated, as many Russians were—and are—by what happened.

We talked about Nansen, too — Nansen is probably far more known to Russians of a certain generation than most other people. After World War I, Nansen as High Commissioner for Refugees led the League of Nation’s first large-scale humanitarian task – the repatriation of 450,000 prisoners of war. Nansen helped refugees to return home, and his work enabled many others to become legal residents and find work in the countries where they had found refuge. One of the issues facing refugees was their lack of a standardized, globally recognized identification document, which in turn complicated their application for asylum. The eponymously named “Nansen passport”, was the first document to validate stateless people. In 1921, Nansen was also tasked with creating a relief program for millions of victims of the famine in Russia and the Soviet Union between 1921-1922. Nansen was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1922. He donated half of his prize money to the humanitarian emergency response in Ukraine.

We talked about Nansen, too — Nansen is probably far more known to Russians of a certain generation than most other people. After World War I, Nansen as High Commissioner for Refugees led the League of Nation’s first large-scale humanitarian task – the repatriation of 450,000 prisoners of war. Nansen helped refugees to return home, and his work enabled many others to become legal residents and find work in the countries where they had found refuge. One of the issues facing refugees was their lack of a standardized, globally recognized identification document, which in turn complicated their application for asylum. The eponymously named “Nansen passport”, was the first document to validate stateless people. In 1921, Nansen was also tasked with creating a relief program for millions of victims of the famine in Russia and the Soviet Union between 1921-1922. Nansen was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1922. He donated half of his prize money to the humanitarian emergency response in Ukraine.

Over tea, 100 years after 1922, my new friend handed me three real Nansen passports. The passports were from Odessa, Ukraine.

“I want you to take these and do something with them. I told my family about your Nansen work. They are OK with me doing this.”

Dumbfounded, I returned home with three authentic Nansen passports in my car, and a strong wish to do something with them that might make a difference in some way. Life works in strange ways, that is certain. A friend of mine, Sasha Laurita, also Russian, was raising money for a Ukrainian family she knew who had lost everything they had and who managed to flee Ukraine to Germany, living on the goodwill of strangers. Irina has three kids, her husband died of cancer a couple of years ago, and they had to abandon their home which they had bought with his life insurance. She was struggling with depression and was just coming out of it just as her town got blown up. She lost everything.

So, with the help of Two Ponds Press—my publisher for Nansen’s Pastport – I had 200 numbered copies printed of this Ukrainian Nansen passport I got in Friendship, Maine, adding some artistic details, and all proceeds went to the Ukrainian family. Could it have gone to a bigger organization helping on the front lines? I suppose it could, but we chose that family because it felt like a tangible goal, using a tangible piece of history. We loved the idea of a family document reaching across generations and an ocean to help another family. The “Friendship Passport” ended up raising $30,000 for this devastated family, and it was an amazing experience to see Nansen’s spirit continue to support displaced people in need.

PDD Secretariat: What role does research play in your creative process?

Anneli Skaar: Research is important, as I would not want to present something inaccurately. However, as I often tell people, I am NOT a scientist nor a politician, and certainly not a scholar on Nansen. As an artist I am simply an observer and interpreter. I try to make ideas and concepts more accessible through narratives which feel more natural and open to human attention, but of course I do make every effort to ensure that information I try to convey is correct.

PDD Secretariat: How do you see your work contributing to discussions in international policy fora like the Global Forum for Migration and Development?

Anneli Skaar: I hope that my artistic work might approach a problem or concept from an unexpected perspective, and in doing so it might expand the way someone might be considering it. To be able to have my art possibly influence policy makers in an unexpected and positive way, even just a tiny bit, feels like a worthy endeavor.

Photos 1,2: courtesy of the artist

Photos 2,3: PDD Secretariat