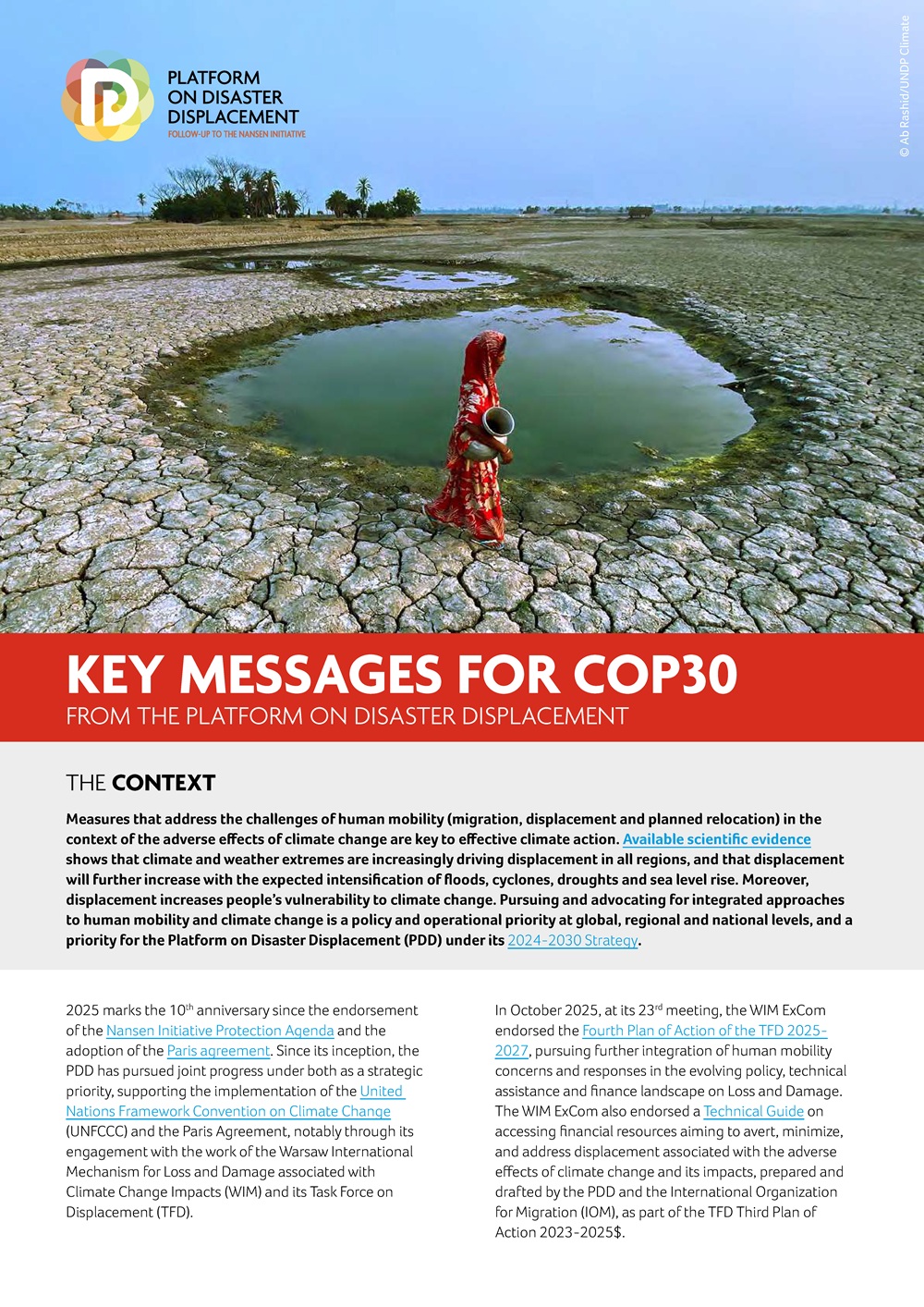

The connection between climate change and peoples’ mobility is increasingly recognized in academic and policy circles, and popular media. Most visible are the impacts of disasterous events such as flooding on forced displacement, but slow onset environmental changes such as sea level rise and changing seasonal weather patterns are nowadays also crucial in shaping human mobility (or ‘environmental migration’) in various ways. In slow-onset processes, the changing climate intersects with other ongoing economic and social development activities and their associated environmental impacts which influence situations of vulnerability, for example the construction of large hydropower dams. As a result, there is significant debate on how to understand the relationship between pre-existing conditions, slow-onset climate change and human mobility. This lack of consensus has implications for law and policy, as well as responses on-the-ground.

Climate change poses threats to human rights, including the right to life, the right to health, the right to shelter, and the right to food, and many others amplifying the impacts of structural inequalities and injustices. There is a growing recognition within human rights literature, international and national law, and among practitioners, of the connection between environmental change including climate change, mobility and human rights. These studies are now establishing a framework for determining the duties of states, and the entitlements of rights-holders. Governments in mainland Southeast Asia are increasingly making commitments and policies on climate change mitigation and adaptation, yet human mobility due to ‘slow-onset’ climate change seems to be less acknowledged and addressed.

This policy brief examines the connections between climate change, peoples’ mobility and human rights in the Mekong Region. A particular focus is on the slow environmental change dimensions of climate change, such as sea level rise and changing seasonal weather patterns, that are shaping peoples’ mobility in less recognized ways. Slow onset processes introduce significant complexity, given that any decision to migrate intersects with pre-existing conditions and other ongoing economic and social development trends. The seeming lack of consensus on how to define and understand this form of ‘environmental migration’ has implications for law and policy, as well as responses on-the-ground. However, a human rights-based approach is emerging that connects together climate change, mobility and human rights.